電子振動:現代技術を駆動する無限のリズムの科学

電子振動:現代技術を駆動する無限のリズムの科学

Electronic oscillations form the foundational heartbeat of modern electronics, enabling everything from pulse-width modulation in power systems to the precise timing in digital communication. These self-sustaining sinusoidal waveforms—generated through feedback mechanisms in electronic circuits—provide the rhythmic precision required for stable, efficient, and high-speed operation. From the simplest LC tanks to complex semiconductor oscillators, the physics and engineering of electronic oscillations underpin innovations that shape how devices sense, process, and transmit information.

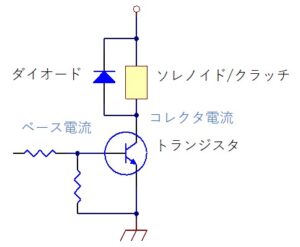

At the heart of every electronic oscillator lies a fundamental principle: feedback sustains and synchronizes energy exchange between reactive components—inductors and capacitors being the most common.

The oscillation frequency, dictated by physical parameters like inductance and capacitance or semiconductor properties, determines the behavior and application of the circuit. This controlled rhythmic movement is not just an abstract phenomenon—it enables synchronization in radar systems, ensures data integrity in clock signals, and powers the high-frequency carrier waves underpinning wireless networks.

Principles and Types of Electronic Oscillations

Electronic oscillations emerge from the interplay of energy storage and dissipation within circuits. The most basic form—自然振動 (natural oscillations)—arises in LC circuits, where a capacitor’s charge release generates alternating current via an inductor’s magnetic field, creating sinusoidal waveforms at resonant frequencies (\( f = \frac{1}{2\pi\sqrt{LC}} \)).

This principle forms the basis of several oscillator topologies, each tailored to specific performance needs.

LC Oscillators: These rely on inductors and capacitors to sustain oscillations at relatively low frequencies. The Colpitts and Hartley configurations exemplify LC oscillators used in radio transmitters and frequency synthesizers. Their predictability and stability make them reliable for applications demanding precision over moderate frequency ranges.

Crystal Oscillators: Unlike passive LC networks, crystal oscillators leverage the piezoelectric effect in quartz crystals, which vibrate mechanically at extremely consistent frequencies when electrically excited.

Operating typically in the MHz range, these oscillators achieve extraordinary accuracy—essential for clocking microprocessors, GPS systems, and communication protocols where timing errors can cascade into system failure.

Phase-Locked Loops (PLLs): Beyond generating raw oscillation, PLLs dynamically lock output frequency to a reference signal, correcting drift and enabling frequency multiplication or division. Used extensively in frequency synthesis, PLLs allow complex signal generation with minimal jitter, making them indispensable in modern transmitters and receiver front-ends.

Square Wave Generators and Schmitt Triggers: Sawtooth and square wave outputs stem from monostable and astable configurations using operational amplifiers or Schmitt-trigger logic. These oscillators produce fast-rising, periodic signals critical for clock generation, pulse width modulation (PWM), and timing control in digital logic circuits.

Applications Driving Innovation

Across industries, electronic oscillations enable core functions that define system reliability and performance.

In telecommunications, stable oscillators coordinate data transmission across cellular networks, ensuring synchronization between base stations and mobile devices. Even minor frequency deviations—measured in parts per billion—can degrade signal integrity or cause data loss.

In radar and electronic warfare, precisely controlled oscillations enable pulse compression, improving target detection and resolution. For instance, modern pulse-Doppler radar systems rely on highly stable microwave oscillators to distinguish moving targets from background clutter through fine frequency discrimination.

In computing, crystal oscillators serve as the system clock, directly influencing processing speed and parallelism.

As data rates climb toward terahertz levels in emerging technologies like AI accelerators and quantum computing interfaces, even nanosecond timing inaccuracies can compromise correctness. This demand pushes oscillator designs toward lower phase noise and broader bandwidth capabilities.

Sensor networks and Internet of Things (IoT) devices leverage low-power oscillators for self-clocking operations and precise timing of data sampling. Here, balance between clock stability and energy efficiency defines system longevity—pioneering designs now integrate commutation oscillators that reduce static power consumption without sacrificing accuracy.

Engineering Challenges and Emerging Frontiers

Despite decades of refinement, electronic oscillations face mounting challenges.

Electromagnetic interference (EMI), temperature drift, and aging effects degrade long-term stability. The pursuit of miniaturization further complicates thermal and parasitic capacitance management, demanding novel circuit schemes and advanced materials like gallium nitride (GaN) and silicon carbide (SiC).

Researchers are exploring optically synchronized oscillators (OSOs) and atomic-clock-inspired electronics for envisaged future networks requiring unprecedented timing accuracy, potentially achieving stability rivaling isolated cesium clocks at tabletop scales. Meanwhile, machine learning-driven digital compensation techniques dynamically correct frequency drift in real time, enhancing robustness in chaotic environments.

Quantum oscillators—systems exploiting quantum coherence to sustain oscillatory behavior—represent a disruptive frontier.

Early prototypes leverage superconducting qubits and nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond, offering oscillation stability defects of yottahertz and potential use in quantum communication networks governed by ultra-precise timing.

“Electronic oscillations are not merely a technical detail—they are the silent rhythm that orders the chaos of signals in modern systems,” observes Dr. Elena Moreau, a leading research physicist in high-frequency circuit design. “Every frequency stability issue, every timing error, arises from imperfections in control mechanisms we must continually refine.”

The role of electronic oscillations extends beyond traditional electronics into emerging domains—from neuromorphic computing, where oscillatory neural networks mimic brain dynamics, to satellite laser ranging, where picosecond timing ensures centimeter-level distance measurements.

Each application hinges on precise control of electronic timing patterns.

As technology advances toward exascale computing, pervasive connectivity, and quantum-synchronized infrastructure, the evolution of electronic oscillators remains a critical enabler. Continuous innovation in materials, topology, and control algorithms ensures these rhythmic foundations will continue delivering the predictable yet flexible timing essential to human progress.

Insight: Electronic oscillations, though rooted in classical electromagnetics, are evolving with quantum precision and digital intelligence. Their mastery defines not just technological capability but the reliability of systems upon which safety, communication, and computation depend.

Understanding their principles and applications is key to navigating the next era of electronic innovation.

Related Post

Alex Cooper Wiki: The Enigma of the Enforcer in Professional Wrestling History

Joe Buck, Fox NFL Star, Reveals Age, Marital Life Behind the Broadcast Screen

/ice-cube-1-435-1-8fd8d5d9e9fa490ea5f88577caad0ef6.jpg)

From Compton to Stardom: Ice Cube’s Son Movies Trace a Powerhouse Hollywood Rise

IMovie in 2025: Still a Video Editing Powerhouse Despite Rising Competition